Knowledge centre

Introduction to causes and consequences of trauma

Trauma darkens people’s lives—worldwide. Much of that trauma remains hidden, especially in the developing world: unrecognized, undiagnosed, and therefore left untreated.

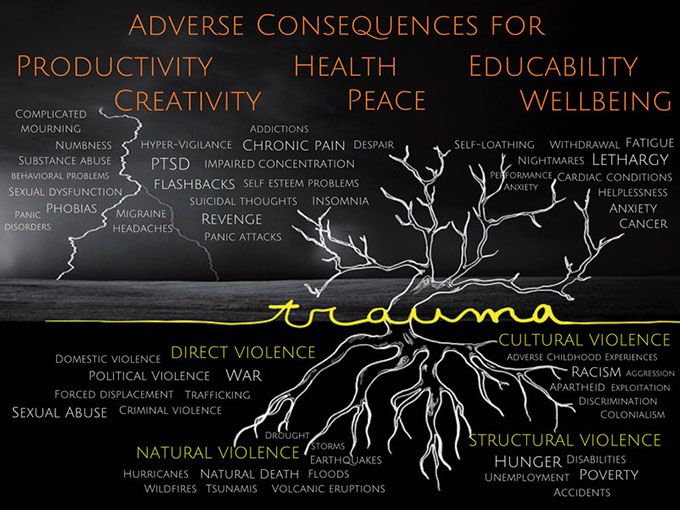

This trauma tree is a visual metaphor of the causes and consequences of traumas and traumatic stress.

The image of this trauma tree shows the origins or causes of trauma, depicted as root systems, which can be grouped into four categories, or ‘Four Violences’, a distinction borrowed from Johan Galtung (1) :

- Direct violence comprises acts intended to harm human beings

- Natural violence, or the violence of nature, in contrast to direct violence, is both unintended and mostly unavoidable

- Structural violence occurs when a social structure harms people and prevents them from meeting their basic needs—physical, economic or social

- Cultural violence manifests itself in prevailing attitudes, based on beliefs about power and ‘necessity’ of violence.

These Four Violences cause the many unseen scars of ‘silent’ and ‘loud emergencies’, of life’s adversities or accidents and of manmade or natural disasters. Those scars are shown here as the trauma-based disorders and diseases, growing out of the leafless branches of the trauma tree.

These trauma-based disorders and diseases affect not only individuals, but also families, communities and even whole societies. They create an ecosystem of profoundly adverse consequences for human development, for world development, and even for world peace.

But much of the world is unaware of these facts, which explains why the response remains far below the challenge that traumas pose.

Although trauma and traumatic stress are not altogether preventable, they can today be much better managed and treated than ever before.

But to actually realize that potential will require a greater consciousness among many stakeholders about the global burden of trauma. And, more importantly, a greater awareness that effective therapy solutions are now available.

To bring those solutions to the millions who need them will require large-scale training of professional, paraprofessional and volunteer workers to identify, manage and treat traumas.

Both consciousness-raising and paraprofessional training present global-scale challenges. GIST-T was set up to help meet those challenges.

(1) -Galtung, J. (2000). Conflict transformation by peaceful means – the transcend method. Geneva: United Nations Disaster Management Training Programme (UN DMTP). Available at: www. transcend.org/pctrcluj2004/TRANSCEND_manual.pdf [Accessed 6 Dec. 2016].

Knowledge centre

Stress, trauma and PTSD

STRESS

This Yerkes-Dodson Stress Curve (2) relates stress levels to performance levels, and shows how rapidly performance declines from a high if anyone is pushed (or pushes him/herself) into stress overload—with potentially serious consequences for his/her health, well-being and even employment.

The mindset of those in the optimum stress zone is often connected to hope and optimism, while the overloaded zone tends to be characterized by thoughts that are rooted in helplessness and hopelessness.

This stress curve also shows that stress becomes negative when it goes on too long, is too severe or occurs too often. All living systems are designed to have periods of activity and rest. When this natural cycle is out of balance, bodies and minds become susceptible to experiencing either extremes of the stress curve.

Stress can be defined as any demand or change that the human system (mind, body, spirit) is required to meet and respond to. Stress is a part of normal life and without challenges and physical demands, life could become boring. Stress becomes distress (or traumatic stress) when it lasts too long, occurs too often, or is too severe (3).

There are many types of stress; for more information, click here

(2) – Yerkes, R.M. and Dodson, J.D. (1908). The Relationship of Strength of Stimulus to Rapidity of Habit Formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, pp. 459-482.

(3) – Lisa McKay, Headington Institute Understanding and Coping with Traumatic Stress

TRAUMA

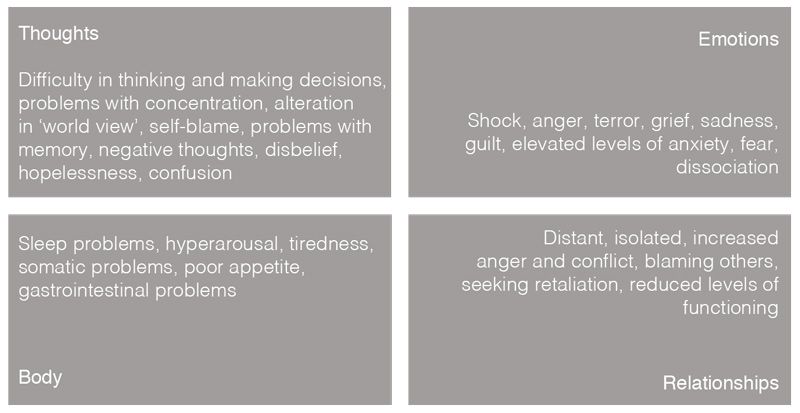

Traumatic stress is caused by events that are shocking and emotionally overwhelming situations that may involve actual or threaten death, serious injury, or threat to physical integrity (4). Such events are generally, but not necessarily, outside the range of usual experience: life is perceived to be under immediate threat, and the individual feels out of control, or he/she witnesses or is subject to an extreme stressor such as violence or a disaster. On occasion this can lead to more serious psychological difficulties. Immediately after a traumatic event, most psychological responses show up relatively promptly. For some people they range from mild and transient, whilst for others they can be extremely strong and disabling. Primary traumatic stress results from directly experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. Secondary, or vicarious traumatic stress, results from interacting with, or helping, people who have been exposed to traumatic experiences.

(4) – International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, http://www.istss.org/public-resources/what-is-traumatic-stress.aspx

PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur after exposure to an extreme stressor(s) where there is the threat to self or others of death, serious injury or sexual violence. It is accompanied by intense fear, helplessness, and/or horror. The traumatic event(s) can be persistently re-experienced through four broad types of symptoms: (5)

- intrusive and distressing recollections, dreams, or flashbacks

- psychological and physiological distress when reminded of the stressor

- avoidance of things associated with the stressor

- persistent symptoms of heightened anxiety such as difficulty falling asleep, irritability, hyper-vigilance, and difficulty with concentration.

These symptoms usually occur within one month of experiencing the traumatic event, although ‘delayed expression’ of symptoms can also occur. (6)

(5) – WHO/UNHCR (2015) mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide, p.28, Geneva. This guide mentions another type of symptom: considerable difficulty with daily functioning.

(6) – American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-5, p. 271-273. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing

Knowledge centre

Two WHO-recommended therapies

There are many approaches to trauma, and many treatments and therapies exist. But only a few are supported by sound and empirical research. The World Health Organization (WHO) to date has recommended only two therapies for the treatment of PTSD: CBT-TF and EMDR therapy (see below).

Individual reactions to Traumatic Stress

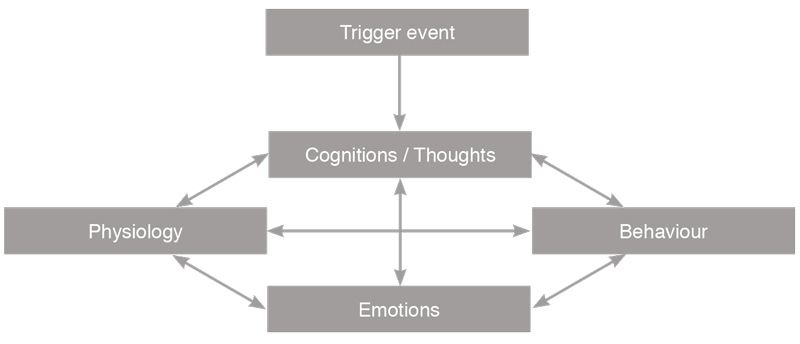

CBT-TF

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy with a Trauma Focus (CBT-TF): This therapy originates from Cognitive Behavioural treatments. It focuses upon the core PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing, avoidance and hyper-arousal by targeting unhelpful and unhealthy thoughts (for example, as when a person considers that they may be to blame for being sexually abused). CBT-TF also examines a person’s patterns of behaviour (avoidance or safety behaviour/increased irritability and anger/becoming withdrawn) and seeks to adjust these. It also focuses upon ‘fear responses’ and tries to modify these towards more healthy responses. For clients who are skilled in presenting their thoughts and emotions through verbal communication, CBT-TF uses these attributes to good effect. CBT has been found to be particularly helpful in cases involving grief and bereavement.

Basic Model of CBT

CBT-TF has a number of components. The mnemonic PRACTICE is useful as a memory aid:

- Psycho-education

- Relaxation techniques

- Affect regulation

- Cognitive coping

- Trauma narrative

- In-vivo exposure

- Challenging safety behaviour

- Enhancing optimal post-traumatic growth

EMDR THERAPY

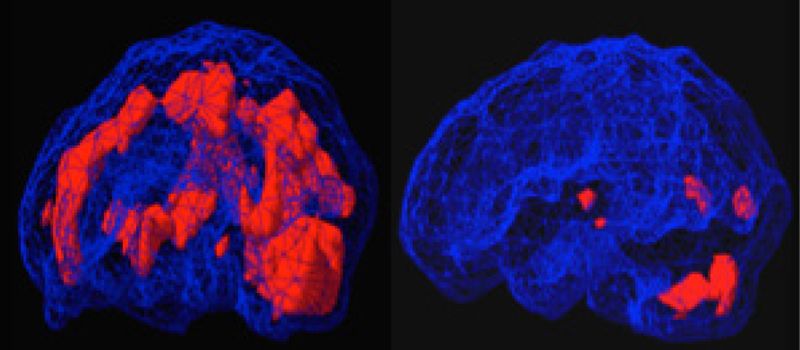

Before and After EMDR Brain Scans

EMDR Therapy: EMDR is the acronym for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, and this therapy is increasingly recognized internationally as an effective psychological trauma treatment. EMDR Therapy is a psychological treatment method that was developed by an American clinical psychologist, Dr Francine Shapiro, in the late 1980s. Shapiro published the first research data to support the benefits of the therapy in 1989. Since then, a wealth of research has been conducted (7) demonstrating its benefits in treating psychological trauma, arising from experiences as diverse as war-related events, childhood sexual and/or physical abuse or neglect, natural disasters, assault, surgical trauma, road traffic and workplace accidents. EMDR Therapy has been found to be of benefit to children as well as adults. EMDR is a complex therapy incorporating bilateral stimulation during the processing of disturbing memories. As Shapiro elaborates:

Old disturbing memories can be stored in the brain in isolation; they get locked into the nervous system with the original images, sounds, thoughts and feelings involved. The old distressing material just keeps getting triggered over and over again. This prevents learning/healing from taking place. In another part of your brain, you already have most of the information you need to resolve this problem; the two just cannot connect. Once EMDR starts, a linking takes place. New information can come to mind and resolve the old problems. This may be what happens spontaneously in REM or dream sleep when eye movements help to process unconscious material. (8)

(7) – See at following link. http://emdria.omeka.net/. For more information see http://www.emdr-europe.org6/info.asp?CategoryID=27

(8) – Shapiro, F. (1995) Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic protocols, principles, and procedures. New York, NY: Guilford (p 219-222)

COMPARING THE TWO WHO-RECOMMENDED THERAPIES

Both CBT-TF and EMDR Therapy are based on empirical evidence and have been scientifically validated as effective. For example, research shows that CBT-TF achieves an 82% remission of single-incident PTSD within 12 to 15 therapy sessions of between 30 to 90 minutes each.(9) Similarly, research shows that EMDR Therapy achieves an 84-100% remission of single-incident PTSD within three therapy sessions of 90 minutes each.10 CBT-TF has long been recognized, but the WHO’s recognition of EMDR Therapy is of more recent date (August 2013).

In comparing the two therapies, some differences become apparent. As the above-quoted WHO assessment implies, CBT-TF has some practical drawbacks that pose extra challenges for scaling up in case of big crises. EMDR Therapy, on the other hand, has some inherent strengths that are especially advantageous under field conditions in resource-poor environments.

EMDR Therapy is often rapidly effective. It requires only minimal contact time – measured in hours and days, not weeks and months. The remarkable speed of EMDR Therapy is notable in resolving both single incident traumas and complex PTSD. Much of the (initial) work can be done in groups, and treatments can be administered on consecutive days. These features are of huge operational advantage in humanitarian settings and peace operations, as disasters and conflicts often produce large-scale and urgent needs. In fact, EMDR Therapy has been used cross-culturally in response to mass natural and man-made disasters. (11) (12) (13) (14) Moreover, EMDR Therapy is often more easily accepted because it is minimally intrusive and does not require the victims/survivors to talk in detail about their traumatic experience, or to do homework (both of which may cause resistance to treatment).15 EMDR Therapy may also be more appropriate for trauma victims who are less used to abstract thinking in everyday life. In fact, when a person is distressed, he/she is not able to engage in abstract thinking. This makes EMDR Therapy additionally appropriate because it has a strong somatic/physical focus: body memories.

There may be another advantage to EMDR Therapy in the context of trauma therapy for military personnel.

[i]n regards to psychotherapies with military personnel, a premium is placed on practicality, flexibility, efficiency, rapidity, and effectiveness within a believable therapeutic framework that is respectful of warrior culture and ethos. To that end, EMDR Therapy appears uniquely suited. (16)

It has also been noted that military clients whose symptoms include guilt, anger or shame may tolerate EMDR Therapy more easily, since the processing is internal to the patient who does not have to reveal the traumatic event.17 However, in general, peacekeeping personnel may prefer the more vigorous CBT-TF because of its robust/’macho’ image.

EMDR Therapy for PTSD may have some drawbacks. During the course of EMDR Therapy, a person re-experiences the traumatic event that triggered the PTSD. For some individuals this can be a stressful and emotionally charged experience, although a therapist is present to help the person manage their emotions. The traumatic feelings may persist after a session is finished and interfere in other aspects of a person’s life.

Given the huge scale of the trauma problem, all possible help from all possible sources should be welcomed: there is more than enough room for both these trauma care/treatment modalities to be applied.

(9) – Jensen, T.K., Holt, T., Ormhaug, S.M., Egeland, K., Granly, L., Hoaas, L. C.,… and Wentzel-Larsen, T., (2014). A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 356-369

(10) – Wilson, S., Becker, L.A. and Tinker, R. H. (1995). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Treatment for psychologically traumatized individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 928-937

(11) – Gelbach, R. (2014) EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Programs: 20 Years and Counting. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(4), 196-204

(12) – Mehrotra, S. (2014) Humanitarian projects and growth of EMDR therapy in Asia. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(4), 252-259.

(13) – Shapiro, F. (2014). EMDR therapy humanitarian assistance programs: Treating the psychological, physical, and societal effects of adverse experiences worldwide. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(4), 181-186

(14) – Zaghrout-Hodali, M. (2014). Humanitarian work using EMDR in Palestine and the Arab world. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(4), 248-251

(15) – When EMDR interventions are given early, they may prevent traumas from accumulating and becoming dysfunctionally stored trauma memories, rather than merely ‘curing’ them; they may strengthen resilience in the context of on-going traumatic events; and since trauma survivors may be more open to treatment soon after the event, early intervention may reduce avoidance, since the majority of trauma-exposed victims with symptoms will not seek treatment. See: Shapiro, E. (2012) EMDR and Early Psychological Intervention Following Trauma. European Review of Applied Psychology, 62, 241-251. Similar benefits of early intervention also apply to CBT-TF. See: Kornør, Hege et al. (2008) Early Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy to Prevent Chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Related Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 8 (2008): 81

(16) – Russell, M. et al. (2013) Treating Traumatic Stress Injuries in Military Personnel – An EMDR Practitioner’s Guide. Routledge

(17) – Ibid.

Knowledge centre

Psychological first aid

In times of crisis, people on the ground are always the first to provide support to those who have been most affected. First Aid for physical ailments is universally recognized. The new global norm is for all first responders to be trained in Psychological First Aid (PFA).

WHAT IS PFA?

There is increasing recognition of the value of early psychosocial support in the aftermath of traumatic events and disasters.(18) (19) Psychological First Aid (PFA) is one evidence-informed approach to offering support to individuals, families and local communities. It covers both ‘social’ and ‘psychological’ support.

PFA is a brief intervention that provides psychosocial support to individuals, families and communities in response to their exposure to a disaster or crisis situation. In doing so, PFA should be both ‘supportive’, carried out with dignity and respect, and mindful of individual human rights.(20) The primary aim of PFA as an initial intervention is to reduce distress, promote basic needs, deliver important information, connect people with available support networks and enhance long-term coping and functioning. PFA assists individuals, families and communities to cope and function better in the short, medium and long-term post disaster or post crisis, by operationalizing the four key attributes of care, comfort, support and hope.

At PFA’s core are active, non-intrusive listening and interaction skills which cover both social and psychological support in the provision of humane, supportive, practical help to people suffering from serious crisis events. PFA is targeted towards vulnerable populations and is considered effective as a means of prioritizing assistance based upon people’s individual needs.

The broader objectives of PFA include:

- Restoring safety – physical health and well-being

- Improving functioning – psychological health and well-being

- Empowering action – behavioural health and well-being

- Connecting with the community – social health and well-being

(18) – WHO (2010) Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548205_eng.pdf

(19) – WHO and PAHO (2010) Culture and Mental Health in Haiti: A Literature Review

(20) – The Sphere Project (2011) Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response. Geneva: The Sphere Project. Available at: sphereproject.org

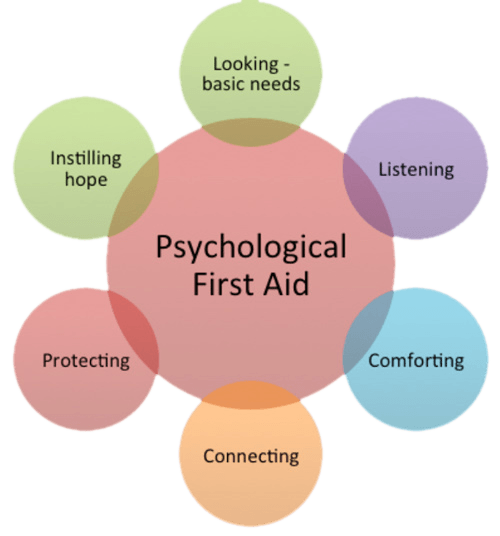

SIX CORE COMPONENTS OF PFA

Since the late 1990s, people working in the trauma-response field have been increasingly using PFA in the aftermath of traumatic events. Even though PFA trauma response may involve rescue, logistics, supply of essential provisions such as food, water, blankets and shelter, the mental health and well-being of survivors is also an important consideration. PFA is based upon principles of common sense in terms of ‘do no harm’ and is part of a broader, community-based intervention specifically designed for field delivery.

PFA uses what is called a ‘triage approach’, which means prioritizing help based upon a person’s individual needs, circumstances, urgency and risk. The goal of PFA is to reduce distress, empower individuals and link them with whatever additional local services and community resources may be available. Ideally, PFA is a means of aiding people to rebuild their own lives following a crisis event.

There are six core components in PFA.

These six core components of PFA are briefly described below. The term ‘PFA worker’ is used here to denote anyone who is working at field level in crisis situations and who is familiar with the principles and practices of psychological first aid, as defined by WHO.

1. Looking – basic needs

This involves providing safety, comfort and support, as well as delivering practical help including food, water, shelter, information and, if necessary, medical assistance. PFA workers should repeatedly offer simple information that is accurate and up-to-date. They should be clear about what resources are currently available, what is not, and what might be available in the future. This information will be on-going as immediate needs and people’s concerns are identified and addressed. Information gathering becomes important for recognizing immediate needs and concerns. This may require addressing issues around safety and security, provision of medical and healthcare services, the need for specific treatment interventions such as medication, first aid, physical treatment, and immediate referral to services, and include the provision of follow-up and continued contact.

Such practical assistance is a vital part of PFA. When survivors are in heightened degrees of stress and anxiety this has the potential to cloud their reasoning and judgment. PFA endeavours to assist individuals to discuss their immediate needs and then consider what can be done to address their specific concerns.

2. Listening

PFA workers need to listen properly to individuals in order to understand their particular situation and specific needs, and to identify the best way of assisting them. To listen effectively helps people to feel heard and understood which in turn can make them feel calmer. This is important if appropriate help and guidance is to be effective.

3. Comforting

People in distress can feel overwhelmed by a crisis situation. It is important to acknowledge their feelings and emotions such as the loss of loved ones or of their homes. When assisting individuals affected by a distressing event then it is important to respect the safety, dignity and rights of the people being helped.

4. Connecting

After crisis events people often experience high levels of powerlessness, isolation and vulnerability. This may be because they are unable to access their usual support systems. Connecting people with other family members, loved ones, friends and members of the local community is a major part of PFA. Individuals with good social support systems tend to cope better post crisis than those who do not have such systems. If a person indicates that prayer, religious practice or support from religious leaders is helpful, then connecting them with their spiritual community is also important.

5. Protecting people from further harm

Protection is when help, reassurance, support and encouragement is provided. It means helping individuals to cope with their needs and concerns. Protection also involves offering essential and relevant information and providing access to resources. It could also mean reducing further exposure to disaster sights, sounds and smells by limiting contact as much as possible. Another important aspect is to be mindful of children as it often helps if they know that parents, family members or trusted adults are protecting them.

6. Instilling hope

Favourable outcomes from using PFA are frequently associated with instilling a sense of hope and a sense of future for individuals. When engaged in PFA a positive approach is essential and often requires encouraging a person to be positive and to focus upon doing what is required to survive and move forward. This is a form of empowerment. Connecting people with their faith-based beliefs may also lead to a more hopeful and positive outlook.

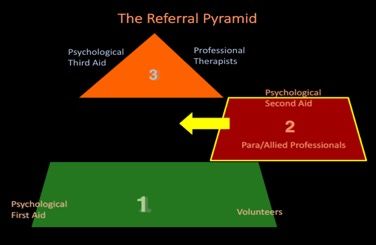

GIST-T AND PFA

Like many other organizations, GIST-T strongly endorses and promotes PFA training—all primary and secondary schools worldwide, and all youth organizations, should incorporate PFA as a life skill in their non-formal education activities. Meanwhile, a distinct feature of GIST-T’s work in this area is to go beyond Psychological First Aid, and to train suitable frontline personnel (such as community health workers, Red Cross/Crescent volunteers, teachers, nurses, doctors, faith-based workers, first-responders, counsellors) in what could be called Psychological Second Aid. That is what the Traumatic Stress Relief (TSR) Training Package and the Confronting Stress and Trauma Resource Kit are all about.

Knowledge centre

Traumatic stress relief

While the humanitarian sector has seen a spike in MHPSS/psychosocial interventions, including PFA on a global scale (21), these are more ‘social’ than ‘psycho’. Despite the existence of effective, evidence-based therapies (22), there is a shortage of MH professionals which is creating an ever-widening treatment gap (difference between need and access) (23).

Targeted psychological interventions for trauma are urgently needed (24) and must be complemented by a strategy to mobilize and prepare suitable frontline workers, both para- and allied professionals, to be trained in simplified techniques to alleviate traumatic stress, and to be able to identify and refer more complicated cases to professional therapists. This strategy makes for a more rational organization of trauma care (fig 1) and will allow for freeing up professionals’ time, so they can give attention to the tasks of training and supervision of para- and allied professionals, and the task of therapy only they can provide.

That way, for the first time, millions of traumatized people will have access to services hitherto beyond their reach or awareness.

fig.1

(21) – Albrecht, D. S., MacKie, P. J., Kareken, D. A., Hutchins, G. D., Chumin, E. J., Christian, B. T., & Yoder, K. K. (2016). Differential dopamine function in fibromyalgia. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 10(3), 829–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-015-9459-4

(22) – de Jongh, A., Amann, B. L., Hofmann, A., Farrell, D., & Lee, C. W. (2019). The Status of EMDR Therapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 30 Years After Its Introduction. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(4), 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.4.261

(23) – Bryant, R. A. (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorder: a state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20656

(24) – Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., & Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 394(10194), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

TASK-SHIFTING

Providing accessible, affordable, evidence-based psychotherapy for trauma is an ongoing and persistent public health challenge. Five decades ago, policy advocates were making comments that echo modern concerns: ‘Professional manpower cannot meet the mental health needs of the population through present methods . . . and there is no reasonable hope that such manpower can be sufficiently increased to do so in the future.’ That shortage of professional wo/manpower, that treatment gap, remains a fact to this day. Thus, the mounting trauma that is suffered, was never near to being significantly reduced, and is increasing due to the global COVID19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine (plus some 60 other violent conflicts), and, more ominously, the looming climate disaster. These are all adding to the number of traumatized people in the world.

The recognition of the problem of capacity shortages in health is not new. It is, however, for mental health. As such, much can be learned from those who preceded us and confronted similar problems. The introduction of Primary Health Care (PHC) in 1978 at the Alma Ata conference, and its application worldwide, has revolutionized physical health planning and practice and resulted in the highly successful Child Survival Revolution (CSR). In view of the shortage of mental health professionals in most LMICs (and even in high-income countries), there are calls to re-allocate human resources to meet the growing need for evidence-based psychotherapy. GIST-T selectively focuses on trauma relief.

‘Task-shifting’ is the key concept here: allowing and sharing simplified, routine task of traumatic stress relief to be performed by properly trained, supervised, and organized para- or allied professionals in the frontline, while at the same time reframing and optimizing the (technical and leadership) roles of the professionals. Task-sharing in this context means involving non-specialists in the delivery of simplified or routine activities of traumatic stress care, thus freeing up professional time for more demanding and complex tasks. Scarce professional resources are thus optimized. As such, task- shifting can make an important contribution to improving access to mental health services (25).

During this past decade the recognition of the need for task-shifting and the use of the new internet-based media has been slowly growing. Task-shifting, together with the new possibilities offered by online connectivity and new technology, holds out the promise that the age-old problems of trauma, with its far-reaching ramifications for individuals and societies, will, this century, become manageable, for the first time in history. There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of task-sharing in psychotherapy; many tasks can easily be delegated to non-specialists which will allow for a redistribution of tasks where professional mental health specialists would become trainers and

supervisors of non-specialist health workers who would identify and provide relief for traumatic stress (26).

Given the promising role of para- or allied professionals in psychological intervention delivery, and given current problems of access to evidence-based trauma interventions, the GIST-T TSR programme, which is based on task-shifting, and uses simplified protocols and techniques, is safe, time-effective, scalable, low-cost, culturally adaptable, and reduces the risk of secondary traumatisation. To read more on the development of TSR, and the prerequisites that must be put in place for scaling up this innovation in terms of safety, effectiveness, efficiency, affordability, and acceptability, please read more In the Current Projects section of this website.

(25) – Stein, D. J., Bass, J. K., Hofmann, S. G., & Ommeren, M. (2019). Rethinking psychotherapy. Global Mental Health and Psychotherapy: Adapting Psychotherapy for Low- and Middle-Income Countries, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814932-4.09998-5

(26) – Hoeft, T. J., Fortney, J. C., Patel, V., & Unützer, J. (2018). Task-Sharing Approaches to Improve Mental Health Care in Rural and Other Low-Resource Settings: A Systematic Review. Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12229

ONLINE BASED TSR SELF CARE PROTOCOLS

FOR MEDICAL STAFF DURING THE COVID19 PANDEMIC

The new Pandemic Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), the acute illness caused by severe respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused unprecedented global disruption, mortality and morbidity. Estimated overall case-fatality rate is 2.3 percent. Most cases are mild with 14% severe and 5% critical (27).

Before COVID-19, only a minority of people with mental health problems received treatment. Studies show that the pandemic has further widened the mental health treatment gap, and outpatient mental health services have been particularly disrupted. The strain of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, and mental health care, is significant. The COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide (28).

To cope with their own traumatic stress, doctors, nurses and other medical personnel can use available self-care techniques, as they too are at high-risk for stress and trauma, either as a direct result of experiencing a traumatic event or being a witness to one. Such self-care is important and will allow them to continue their much-needed work in caring for others. First steps have been made.

(27) – Pal, R., & Banerjee, M. (2020). COVID-19 and the endocrine system: exploring the unexplored. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 43(7), 1027–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01276-8

(28) – Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. (n.d.). Retrieved July 11, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1

Knowledge centre

Resources

TALKS AND PRESENTATIONS

Jon E. Rohde: ‘If we could do it, so can you— Lessons from the Child Survival Revolution’

Global Summit Conference, EMDR Early Intervention, Boston, 20-22 April 2018

An insightful presentation by one of the architects of the Child Survival Revolution on things not to forget when unleashing a Trauma Relief Revolution

Rolf Carriere: ‘Global Needs & Opportunities for EMDR

Global Summit Conference, EMDR Early Intervention, Boston, 20-22 April 2018

A presentation arguing the need for scaling up trauma therapy by training and integrating paraprofessional frontline workers into the mental health system

Rolf Carriere: ’The Now and Coming Traumas— How do we respond to this world challenge?’

Francine Shapiro Memorial Lecture, EMDR Association UK & Ireland Virtual Conference, Cardiff, 13 June 2020

A presentation to highlight the urgency of task shifting from professional therapists to para/allied professionals some simplified treatments to deal with the massive backlog and coming traumas

Rolf Carriere: Notes (with definitions, assumptions, calculations, prevalences), 6 p.

This Note accompanies the Memorial Lecture and helps in understanding the basic assumptions made in calculating the guesstimate proposed in the lecture.

Dr Francine Shapiro interview on EMDR (ABC News, 2017)

Rolf Carriere: ‘Healing Trauma, healing humanity’.

TedxTalks. (2013). Healing trauma, healing humanity: Rolf Carriere at TedxGroningen.

Vikram Patel: ‘Mental health for all by involving all’

Patel, V. (2012). Mental Health for all by involving all.

TEDglobal.

FURTHER READING

Figley, C.R. (Ed). (2002). Treating compassion fatigue. New York: Routledge.

Gerhardt, S. (2004). Why love matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Karr-Morse, R. (2012). Scared Sick: The role of childhood trauma in adult disease. New York: Basic Books.

Rostaminejad, A. et al (2017). Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing on the phantom limb pain of patients with amputations within a 24-month follow-up

Shapiro, F. (2012). Getting past your past: Take control of your life with self-help techniques from EMDR therapy. New York: Rodale Books.

Stein, D. J., Bass, J. K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2019). Global mental health and psychotherapy: Adapting psychotherapy for low- and middle-income countries. In Global Mental Health and Psychotherapy: Adapting Psychotherapy for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-01830-X

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Penguin.

Pupat, A. (2021). Global Initiative for Stress and Trauma Treatment – Traumatic Stress Relief Training for Allied and Paraprofessionals to Treat Traumatic Stress in Underserved Populations : A Case Study. European Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100229

WHO (2020). What do we know about community health workers? A systematic review of existing reviews. Geneva: World Health Organization; (Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 19). Licence: CC BY- NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo.

Woodbury, Z. (2019). Climate Trauma: Toward a New Taxonomy of Trauma. ECOPSYCHOLOGY 11 No. 1, March 2019.

Xiong, T, Wozney L, Olthuis J, Swati Singh R, McGrath P (2019). A Scoping Review of the Role and Training of Para-professionals Delivering Psychological Interventions for Adults with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. J Dep Anxiety 8:342. doi: 10.35248/2167-1044.19.8.342

LINKS

Trauma Information Pages. Baldwin, T. (2016). [online] Trauma Pages.

Available at: www.trauma-pages.com/

IRIN. (2016). The inside story on emergencies. [online] IRIN Humanitarian News.

Available at: www.irinnews.org/

Sage Journals. (2016). Traumatology. [online] Sage Journals.

Available at: http://tmt.sagepub.com/

The Trauma Project:

https://www.facebook.com/The-Trauma-Project-249222445101726/

National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Science:

DIRECTORIES

Directory of Countries and Regions where EMDR has Formal Organizations

- EMDR Argentina

- EMDR Australia

- EMDR Austria

- EMDR Belgium

- EMDR Brazil

- EMDR Canada

- EMDR Colombia

- EMDR Denmark

- EMDR France

- EMDR Germany

- EMDR Hong Kong

- EMDR India

- EMDR Israel

- EMDR Italy

- EMDR Japan

- EMDR Mexico

- EMDR Singapore

- EMDR Spain

- EMDR Sweden

- EMDR Switzerland

- EMDR UK and Ireland

- EMDR Ukraine

- EMDR Uruguay

Regional EMDR Organizations:

- EMDR Institute (Global): emdr.com/emdr-organizations.html

- EMDRIA: emdria.org/

- EMDR Europe: emdr-europe.org/info.asp?CategoryID=48

- EMDR Ibero America: emdrtherapistnetwork.com/emdria.html

- EMDRIA Latinoamerica: emdr.org.ar/

National rauma Aid Agencies associated with EMDR:

- Trauma Aid Europe https://trauma-aid-europe.org/about-us/

- Trauma Aid Netherlands https://www.trauma-aid.nl

- Trauma Aid UK https://www.traumaaiduk.org

- Trauma Aid Germany https://www.traumaaid.org

- Trauma Aid Switzerland http://www.hap-schweiz.ch/hap.php

- Trauma Aid France https://www.trauma-aid-france.org/page/866956-l-association

- Trauma Aid Belgium https://traumaaid.wordpress.com

- emdrassociation.org.uk/home/index.htm

For websites of each of the 24 European country EMDR organizations, please visit emdr-europe.org, then go to ‘About EMDR Europe’ which shows a map with 24 pins which, if clicked, reveals their respective sites. For other countries, please Google ‘EMDR-[country name]’.

Most country websites also offer information about the geographical location of EMDR-licenced therapists.

Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies

Australian Association for Cognitive and Behaviour Therapy (AACBT)

British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP)

Canadian Association of Cognitive and Behavioural Therapies (CACBT)

The European Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies (EABCT)

European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

https://www.estss.org/about/member-societies/#H1

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

http://www.istss.org/home.aspx

National Association for Cognitive Behavioural Therapies

Contact us

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR A.I

Rolf Carriere

OFFICE ADDRESS

GIST-T

c/o Rolf C. Carriere

Van Ommerenpark 164

2243 EW WASSENAAR

THE NETHERLANDS

GLOBAL INITIATIVE FOR STRESS AND TRAUMA TREATMENT - GREATER GENEVA